TLB & Huge Page

Table of Contents

Introduction

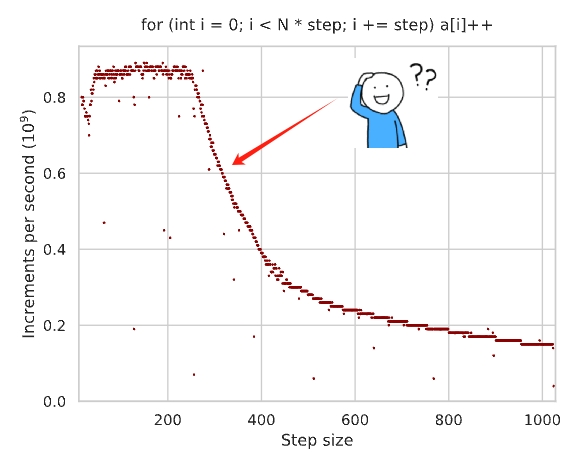

Let’s motivate the topic with a simple experiment.

Suppose we have a snippet of code as follows:

const int N = (1 << 13); // 8k

int a[D * N];

for (int i = 0; i < D * N; i += D) {

a[i] += 1;

}

Then we vary the step size D and note down the time taken to finish the program. Notice only the array size a[D * N] increases. The total iterations remains N times.

What would the performance be like as we vary the step D from 2 to 1024?

The performance drops quickly around step size D=256. The initial thoughts of many people, including myself, is: “Oh this makes sense. As the step size gets bigger, it is using the spatial locality of the data cache poorly. No wonder.”

But if we look closer, this test cpu has 32KB L1 cache, 512KB L2 cache and 16MB L3 cache. Hence, after step D >= 16, each access will be on a difference cache line (16 * 4 = 64 bytes). In total it will retrieve N cache lines covering N * 64 = 512KB data, which fits exactly into L2 cache.

So the performance plot should have been a flat line after step size D >= 16. Something else is misbehaving here.

Memory Paging 101

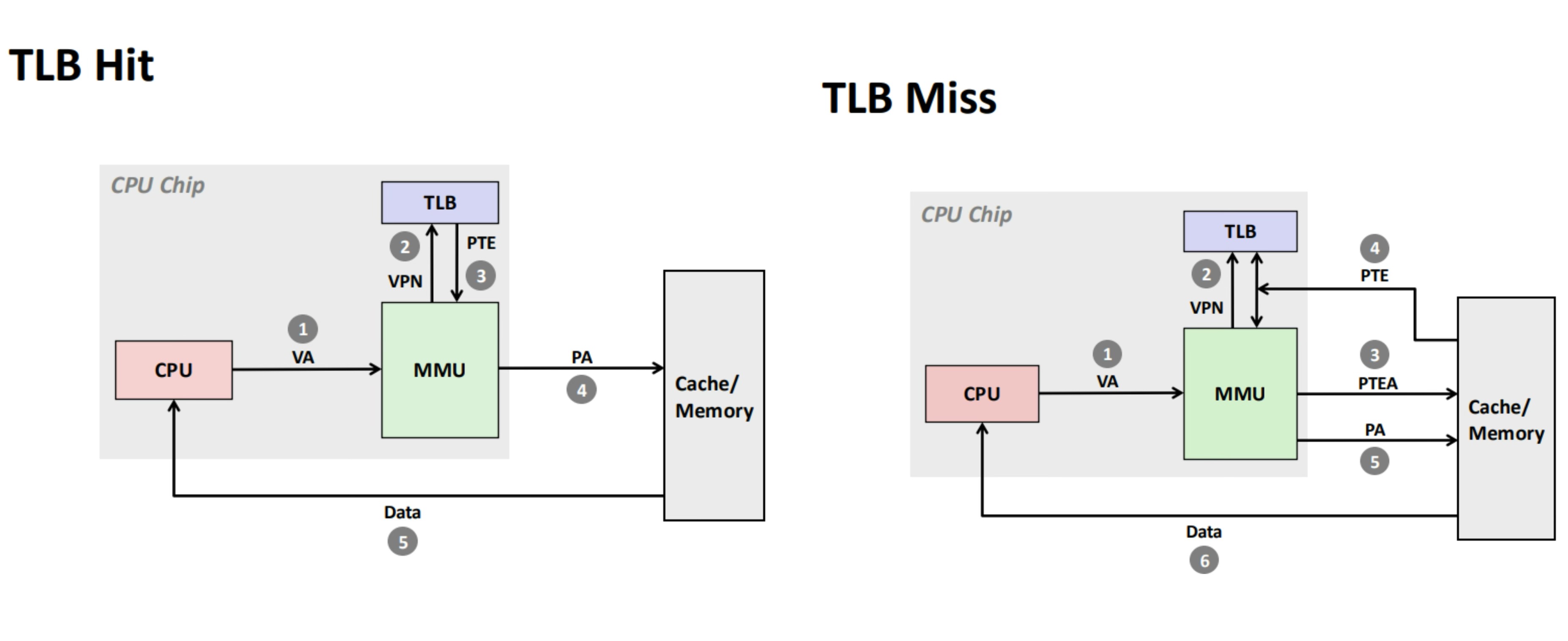

In modern OS, each process uses virtual memory for isolation and multiplexing purposes. The MMU (memory managament unit) on cpu helps to translate the virtual memory address to physical memory address. A small set-associative hardware device called TLB (translation looksaside buffer) helps MMU to cache a few most recently translated mapping from virtual address to physical address. The granularity of mapping is per page, which defaults to 4KB on Linux x86-64.

In the case of a TLB hit, the MMU could save all the works it otherwise needs to perform in the case of a TLB miss.

Now looking back to the experiment, the test cpu has 2048 entries in L2 TLB. With default page size being 4KB, it could cover a range of 2048 * 4KB = 8MB memory.

When the step size D=256, the total size of the array is N * D * sizeof(int) = 213+8+2 = 8MB. It breaches the L2 TLB size and basically lose the ability of caching during memory mapping.

We cannot change the fact that there is 2048 entries in the L2 TLB, unless we buy a new hardware. This leaves us with only one option - enlarge the page size.

Huge Page Comes to Rescue

On most Linux system, the default page size is 4KB. But there are also configurable 2MB and 1GB huge pages.

We can check the default page size via

# check the default page size

$ getconf PAGESIZE

4096

# check the huge page size

$ grep -E "HugePages_Total|Hugepagesize" /proc/meminfo

HugePages_Total: 8192

Hugepagesize: 2048 kB

There are 2 immediate benefits of using huge pages

- Reduced TLB pressure: the memory range TLB could cover will increase from

8MBto 2048 * 2MB =4GBin this case. More likely to get TLB hits. - Even in TLB miss cases, 1 less dependent memory lookup during paging. (4 level paging becomes 3 level paging. 9 extra bits are consumed as byte offset in the enlarged page)

There are 2 common methods to use huge page.

method A

Since Linux 2.6.38 over 10 years ago, Transparent Huge page (THP) is commonly available. It has three modes: always, madvise, never.

We can check the system setup via

# my host is setup in madvise mode

$ cat /sys/kernel/mm/transparent_hugepage/enabled

always [madvise] never

In always mode, most memory allocated by programs is eligible to be backed up by huge pages. But this decreases the memory granularity. Generally not a good idea.

In madvise mode, programs must explictly suggest to OS which chunk of memory should be backed by huge pages.

// sample usage

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

void *p;

posix_memalign(/*memptr=*/&p, /*alignment=*/hugepage_size, /*size=*/array_size);

madvise(p, array_size, MADV_HUGEPAGE);

method B

Another way to employ huge page is through the pseudo file system called hugetlbfs on Linux. It has the following attributes:

- maintain a pool of pre-allocated huge pages

- programs need to explicitly request memory from the hugetlbfs pool

- pages allocated are pinned in memory and won’t be swapped out to disk

# check if it is setup

$ mount | grep hugetlbfs

hugetlbfs on /dev/hugepages type hugetlbfs (rw,relatime,mode=1777,pagesize=2M)

// sample usage

#include <hugetlbfs.h>

#include <sys/mman.h>

void *p = mmap(NULL, size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_HUGETLB, -1, 0);

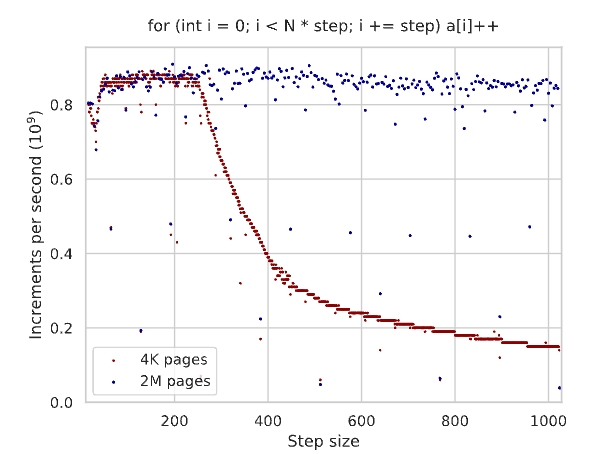

Back to the experiment

Now let’s come back to the experiment and configure it to use huge pages.

const int N = (1 << 13); // 8k

// int a[D * N];

int *a = mmap(NULL, 4 * D * N, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_HUGETLB, -1, 0);

for (int i = 0; i < D * N; i += D) {

a[i] += 1;

}

Mission accomplished!

Caveats

While huge page is a nice optimization for many applications, it comes with its own caveats

- Memory fragmentation: lead to or worsen allocation failure if system’s memory is heavily fragmented.

- pressue on other processes: since huge page non-swappable, less legroom and more thrashing for others.

- operational challenges: tune the right amount of huge page numbers.

- latency spike + sudden memory consumptions during

fork() + Copy-on-Write

Reference

- https://www.hudsonrivertrading.com/hrtbeat/low-latency-optimization-part-1/

- https://www.hudsonrivertrading.com/hrtbeat/low-latency-optimization-part-2/

- https://en.algorithmica.org/hpc/cpu-cache/paging/

- https://people.freebsd.org/~lstewart/articles/cpumemory.pdf

- https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~213/lectures/11-vm-concepts.pdf